Why Icelandic?

The modern Icelandic language, a principal heir to the Norse civilization of the Viking era in ninth- and tenth- century Europe, is essential to an understanding of our Anglo-American heritage as well as that of the modern Nordic nations. While modern Danish, Norwegian and Swedish evolved from the Old Norse spoken and written in several dialects a thousand years ago in Scandinavia, Old English received a massive infusion of Old Norse vocabulary during the Viking occupation of much of England known as the Danelaw (see “Legacy of the Vikings,” by Elaine Treharne), which endured for much of the nine and tenth centuries and even into the eleventh.

The closeness of Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse—kindred peoples, kindred tongues—precludes certainty with regard to the Old Norse component as it has survived into modern English, but the contribution may account for twenty to thirty percent of the modern lexicon. A casual skimming through a modern Icelandic-English dictionary repeatedly confirms the linguistic proximity (see, for an outstanding example, Sverrir Hólmarsson, Christopher Sanders and John Tucker, Íslensk-ensk orðabók = Concise Icelandic-English Dictionary (Reykjavík: Iðunn, 1989)).

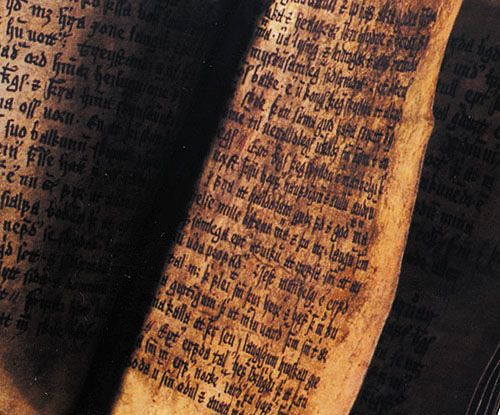

Today’s Icelandic language is closer by far to the language of the Old Norse-Icelandic sagas, which were written down chiefly in remote Iceland, than our English is to that of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. (The degree of insularity is a function of location.) Nonetheless, modern Icelandic is thoroughly modern, befitting a nation that is thoroughly familiar with Anglo-American culture (virtually all Icelanders are fluent in idiomatic English) and digitally savvy (according to “Internet World Stats,” 301,000 Icelanders—97.6 percent of the population of 310,000—were Internet users in mid-2011, compared with 78.2 percent in the United States and a 30.2 percent world average).

Still, the number of books published per year in Iceland is a saga of its own. According to the “Statistical Summary of Material Published in Iceland in the Year 2010” (latest available), the country published 1700 titles, 1450 of them in print format, or one new book for every 213 citizens. These included 476 works of fiction and 81 books of poetry—again, from a population of around 320,000, including preliterate infants.

According to a Bowker information summary, new book titles and editions in the United States (according to the traditional way of counting, i.e. excluding a host of reprinted material) were projected in 2009 to tally 288,355, or one new title per 111 citizens. In terms of books per number of citizens, the United States’ lead is hardly surprising—but derives from a population a thousand times larger than that of Iceland.

Impressive as well are the quantity and quality of Icelandic literature translated into other languages, including English. Not that the task is always easy: see the article on Victoria Cribb, a respected translator.